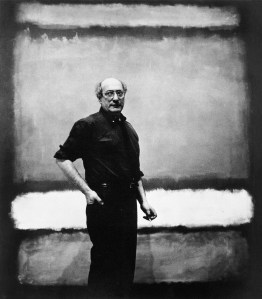

An article by David Levine in Triple Canopy offers an account of the Rothko trial in what is perhaps the most clear, concise and detailed overview yet written about the scandal. Mr. Levine, the son of Morton Levine, among the first directors of the Mark Rothko Foundation, writes “I’m going to break this down very simply, and as nonlibelously as possible.”

An article by David Levine in Triple Canopy offers an account of the Rothko trial in what is perhaps the most clear, concise and detailed overview yet written about the scandal. Mr. Levine, the son of Morton Levine, among the first directors of the Mark Rothko Foundation, writes “I’m going to break this down very simply, and as nonlibelously as possible.”

The Rothko scandal is ones of those messy webs of unfortunate decisions and backstabbing that seems more at home in a Raymond Chandler novel than in reality. Shortly after Rothko’s suicide in February 1970, his estranged wife died unexpectedly of a heart attack. An inconsistency in Rothko’s wills split up his orphaned children. His 19-year-old daughter became the ward of Herbert Ferber. His seven-year-old son Christopher went Mr. Levine’s parents.

To make things more complicated, “Rothko died with his market value climbing and with 798 finished paintings in his studio,” Mr. Levine writes. According to Mr. Levine, a feud with his daughter—in which she announced she hated her father’s paintings—made Rothko decide to leave his work with his three friends, Bernard Reis, Theodore Stamos (a fellow painter), and Mr. Levine’s father. Within three months, the executors of his estate, and now the directors of the Rothko Foundation, sold the entire batch of Rothko paintings to Marlborough Fine Art for $12,000 a piece. Rothko’s prices at this time were often selling for four times that amount, sometimes even in the low six figures. Suspiciously, five weeks after Rothko’s death, Reis was named Marlborough’s director and Stamos joined the artist roster. Rothko’s children, under New York state law were entitled to half their father’s estate, despite his will. They filed suit on November 8, 1971. Marlborough had already sold 36 Rothko paintings at a profit of $2,474,250. Now things got even messier. The trial, Mr. Levine writes, hinged on a single question: “Was Mark Rothko an artistic genius?” A “parade of experts and luminaries,” including Arne Glimcher, Richard Feigen and Meyer Shapiro, all testified on behalf of Rothko’s place as a master painter. The court decided, after three years of testimony, that all Rothko canvases were valued at a minimum of $90,000.

Mr. Levine’s history is sharp and objective. It is hardly a defense of his father, who found himself unwittingly wrapped up in the affair (he resigned his directorship when Reis and Stamos decided to join suit against the artist’s children), nor does it cast Rothko as a hero who was posthumously manipulated by his friends.

Why are we all fighting so fiercely on behalf of bad fathers? Rothko was, by all accounts, a terrible parent, who alienated his teenage daughter to such an extent that she told him she hated his paintings. So he responded as any narcissistic, alcoholic, monomaniacal abstract expressionist would, and he left the paintings in the hands of his friends. Once he’s dead, she’s sorry, and she wants to take it all back. But by now the paintings are with others, who have their own interests and their own understanding of his priorities…Was my dad guilty? I think he was lazy; I think he was negligent.

It’s the stuff of great courtroom dramas. Read it all here.