Attending the 2019 Congress of the International Research Society for Children’s Literature was an utterly amazing experience. Both Stockholm itself and the Congress located in Norra Latin—a historic high school now turned conference center in Norrmalm—offered me a continuous deluge of warm collegial camaraderie, stunning urban and riverside views beneath an overcast sky, scholarship that advocates for the marginalized in all its forms—and coffee, lots and lots of coffee… There were so many things about the trip that offered me a chance to feel at home. Yet, of course, I wasn’t home, and the trip also constantly reminded me of my foreignness, from pedestrian-car interactions (no stop signs!) to prices in krona, and from the sight of cathedrals and cobblestones and the letter “å” to the unremitting child-consciousness of Swedish culture. This is why for my first post-Stockholm post, I decided to explore a children’s book that deals more intensely with the concept of foreignness.

The Arrival

by Shaun Tan

Hodder Children’s Books (2006)

Text: None! This is what one might call a wordless graphic novel, each page filled with pictures in various orientations. I had heard of this book before, though never read it, and then it came up in a keynote presentation on the second day. While browsing a book display during one of our frequent fika coffee breaks, I saw the recognizable cover picture accompanied by a single unexpected word, “Ankomsten”, the Swedish translation of “The Arrival”. For a moment I felt like the quizzical man on the cover, staring at a little alien creature, considering the odd mixture of familiar and unfamiliar that a foreign word can conjure.

Picture: The pictures are arresting, powerful, and intricate, rendered in muted tones and depicting a fantasy/futuristic setting that nevertheless references turn of the century America, specifically the experiences of immigrants passing through Ellis Island. The basic idea behind the book is that there is a man who leaves his family and travels to an entirely new metropolis, a place where absolutely everything is unfamiliar, strange, and foreign. He—and we as readers—struggle to make sense of this new place as the character seeks food, shelter, work, and above all human connection. Gradually and with the help of kind people he comes to understand the ways and codes of this place, reminding me of a George MacDonald quote from Lillith: “The only way to come to know where you are is to begin to make yourself at home.” It is a timely, challenging, and moving book, important for children and adults alike to engage with.

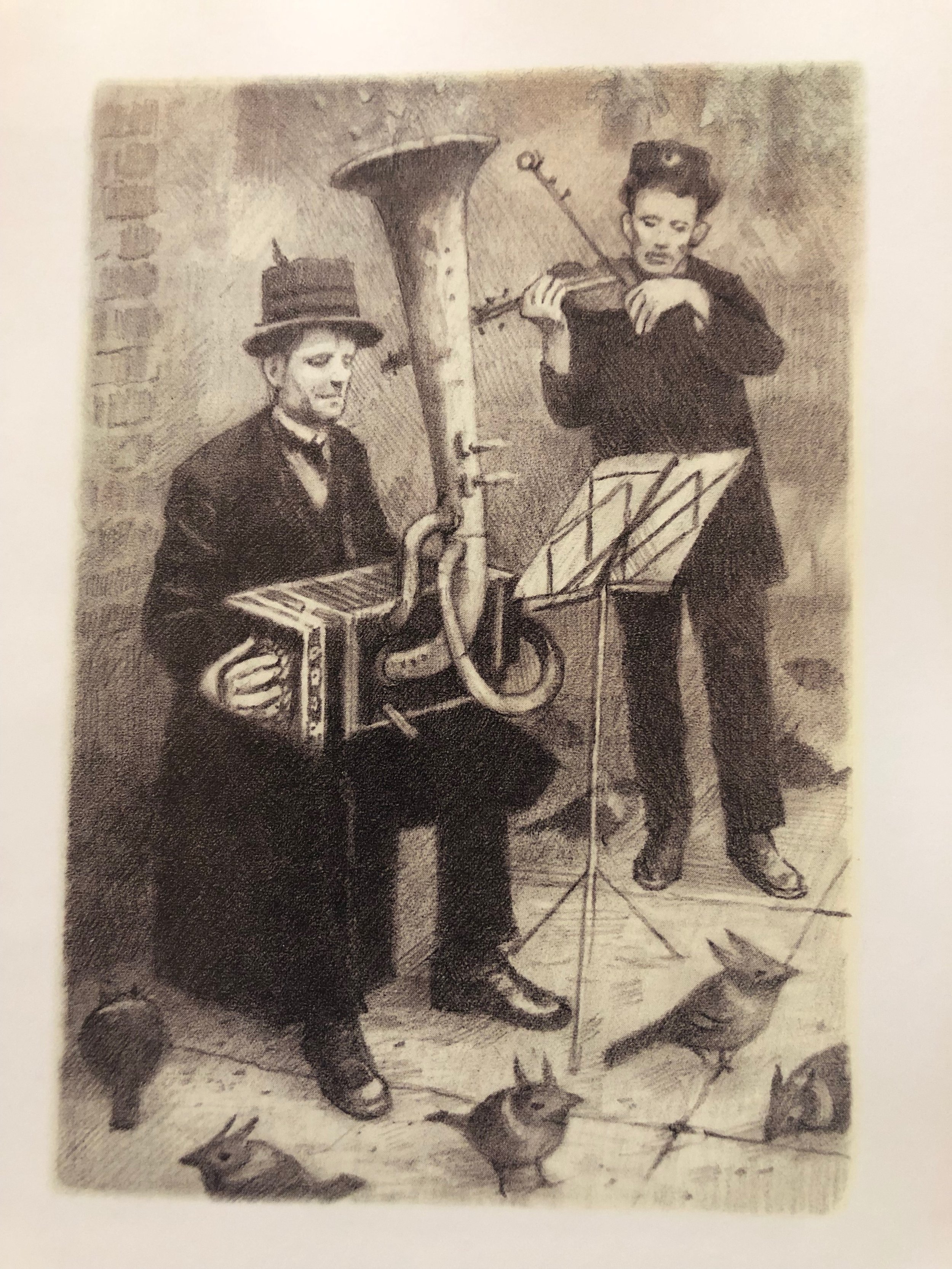

Music: This book entrenches readers in the complex and painful process of learning, specifically of learning to navigate through and within an unfamiliar culture. Music, as an expression and carrier of culture, appears twice in the book and vividly communicates this shift from confusion to understanding. The first picture below depicts the arriving man’s first encounter with this new world.

The man is confused at this point in the story, and we are thrust with him into the middle of an alien world. The invasive protocols of immigration services, the goings-on of bustling people in the streets, the appearance and behaviors of new animals, everything is overwhelming to his senses. The street musicians appear ominous: rendered in very dark hues with dower faces and surrounded by rat-like birds, the otherworldliness of the instruments they play—which include a space-age violin and an accordion with a serpentine tuba bell—is palpable. The concept of “noise” is useful here, as is an oft quoted definition by Anna Tsing: noise is the “awkward, unequal, unstable creative qualities of interconnection across difference” (Tsing 2004, 1). The oddity of the picture and the imagined music—some of which seems to be visibly shooting up out of the tuba bell into the sky—is meant to create a wall of noise. Unsettled by difference, the man has no opportunity to come to grips with its discomfiting significance.

[Aside: Tan’s imagined world of organological difference is actually remarkably similar to our own world. Modern western culture has a very limited notion of what instruments are “normal”, and in the margins of time and space lie instruments that display the human capacity for imaginative music- and/or noise-making. Below: A) a French piano accordion from 1880s on display in MIM Phoenix, B) John Matthias Augustus Stroh’s mechanically amplified Stroh violin invented in 1899, C) Adolph Sax’s trombone à pistons from 1876 on display in MIM Brussels, E) a ca. 1900 harp-guitar by Cesare Candi of Genoa, and F) Linda Manzer’s 42-string Pikasso guitar of 1984.]

The next musical encounter in The Arrival offers fresh possibilities for the newcomer on his journey towards musical and cultural understanding. After befriending a family and learning their own traumatic story, he is invited to dinner. Shared food, conversation, and laughter lead to an after-dinner musical concert, and a new relationship to this culture’s music. We see each member of the family happily contributing to this delightful Hausmusik experience. The father plays a miniature version of the street musician’s trumpet accordion, the mother plays a turnip-shaped ocarina with glowing orb of musical warmth, and the son sings—with his Pokémon lizard!—while strumming on a four-stringed circular guitar reminiscent of a Chinese ruan.

The newcomer’s relationship with this family offers him a bridge toward understanding the meanings of music in this foreign place. Within the safety of a warm domestic setting he is able to draw near enough and to sit still long enough to listen with open ears and to ask questions of the performers in order to approach understand. Tan’s two images of music in The Arrival illustrate the contextuality of whether we interpret something as noise or as music. Relationship opens the door.