Looking at Sustainability

Published in APLD Magazine — Design Online — Mar. 2020

For years I’ve looked at sustainability through the tint of a Landscape Designer’s view. And, like many of you, read or dialogue with other professionals on best ways I can contribute to the cause as a professional. I’ve also been asked to speak on sustainability and been involved in numerous groups who seek to add to the conversation outside of the green industry. And I find myself feeling at times as if my understanding of sustainability or my academic perspectives is separate from my practice as a designer. It’s the ongoing struggle of weighing what is informed with what is practical. I have yet to completely settle on a balance, and seeing what we have seen, I feel safe to assume the constant progressive nature of sustainable dynamics will keep us from settling in any final way. This is a moving target. The goal with the next few articles is to look at sustainability through a new lens tinted this time by the informed not the practical. The hope is that those of you more innovative types take this information and apply it to practical situations, later bringing me back amazing stories to inform our discipline moving forward.

When I do speak, I typically begin with a definition of some kind, mainly because most audiences have a misconception of sustainability. Sustainability isn’t eternal or perpetual. It is typically linear just as most things we conceptualize on earth with a beginning and end, even if those points are outside of our human perspective. Sustainability doesn’t assume other environmental issues that swirl around it like, net carbon 0, native movements or green initiatives. Additionally, in order for something to be sustainable we typically have to sustain it. Which seems kind of ironic in a way. With that in mind I’ll add that due to humanities observation of an ever-changing Earth and the startling shifts that threaten it’s health, as well as our species, a goodly number of bright minds have done well to understand sustainability and the role it plays in our society.

Figure 1 – Venn Diagram of Sustainability

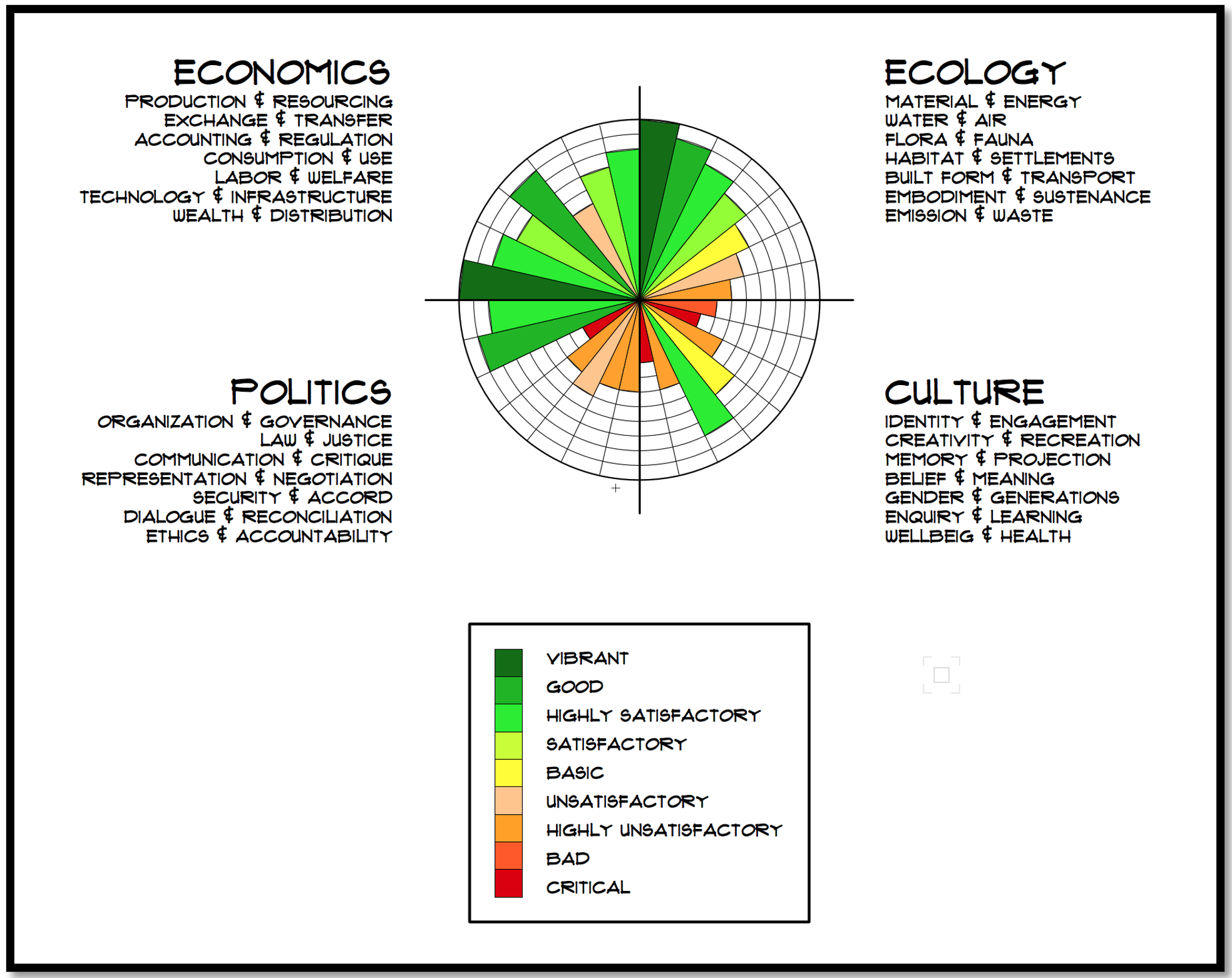

Early studies in sustainability developed a Venn diagram with three main pillars for sustainability. Economic, Social and Environmental. When economic and social overlap we have equity, when social and environment cross it is bearable, when environment and economic cross we have something viable. And only when all three of these cross do we achieve true sustainability, something equitable, bearable and viable, see figure 1. Over time this concept was broadened and built into a more complex model that helps measure successfully implemented sustainable interventions at a large scale. Developed around 2008 we now view sustainable development not as three pillars but as four categories that are laid over nine increasing circles, see figure 2, called Circles of Sustainability.

Circles of Sustainability is often used to assess larger development such as towns, cities, campuses, communities etc. However, it still informs us as planners on both the greater view of sustainability as well as the dynamic moving parts within sustainability that could inform our work. For instance, the four categories are: Ecology, Economics, Culture and Policy. Most of us, active in the industry, find our sustainable energies concentrated on Ecology first, economics second possibly policy third (depending on our location) and often put culture last.

Ecology is extremely important and what I actually would see as the center of the circle, however I didn’t design it. In my mind the purpose of sustainability is ecology. However, ecological sustainability alone does us no good. I think we also can easily wrap our heads around economics. If our work can’t be afforded now or in the long run its integrity will be limited. I recognize the power of technology and time as it pertains to economic sustainability. Not too many years ago LED bulbs were passed up by clients due to cost or complexity. Now they are nearly standard. Ecological and economic sustainability hinge, at the center of this model, on policy and culture and I don’t think that’s an accident.

I recall some 25 years ago one of my first meadow designs and installations. It came in fantastically, wild, natural even shapely in the way I played with it bordering the property edges. The goal was simple, I wanted to limit sod and increase biodiversity in a way that fit into our mid-west setting. However, it was wild and natural. Come to find out that wasn’t the view of my client and within two years time he had cut it all out and replaced it with sod. To some degree I see this as a reaction to the times as that popularity had yet to fully catch on. I see it as his inability to grasp the vision too. But, to a greater extent I blame myself. I didn’t assess a number of things that would help keep the meadow sustained. In this case it wasn’t economics. He was adding to his mowing, which in turn added to his cost and his carbon footprint. It was culture. I could have done a better job priming him, or had a longer dialogue assessing its viability in terms of his expectations. If I had done my client homework better and come to a point that informed eminent failure maybe I could have found a middle ground.

Those are all possibilities. But at the end of the day it’s a small example to the power of culture and policy in terms of sustainability. Many municipalities have policy in place that limit things like non-permeable surfaces. California is buying back lawns for arid plantings. Policy can truly complicate our lives, however I hope they’re in place to give us longer-term success as a society. But, all of that is driven by culture. At the end of the day culture drives policy, economics and ultimately ecology in many ways. Additionally, in our discipline we work directly with a finite set of stakeholders. We work hand in hand with families who put a great deal of value in their space and likely its sustainability. However, the culture of our clients comes with some twists and turns. They play as big a role in landscape sustainability as anyone. They also are an avenue of information that can be congested. Getting to the bottom of what they envision is arduous yet vital. And I don’t wonder if as a group we fail at giving this dynamic enough time or attention in our discussions about sustainability.

This brings us to a crossroads of how we move from the larger-scale to the residential homes that the vast majority of us at the APLD work within. It just so happens a couple of researchers at the National Autonomous University of Mexico did some work that was published in 2013 on sustainable residential environments. Specifically their work was in the area of social sustainability, and they developed a model for Habitability. Next month I’ll take a look at that with you and unpack the cultural dynamics in residential sustainability as we build a solid underpinning before slipping back into the ecological topics that naturally excite us.

Figure 2 – Circles of Sustainability – A sample