Eadweard Muybridge's studies of speeding horses and wrestling men are well known, as is the fact that his photographs were the first to prove that when a horse gallops, there is a stage in its gait when all four legs lift off the ground.

Less well known are details of his colourful life – including that he shot dead his wife's lover and abandoned his child to an orphanage – and his artistic career, which encompassed spectacular landscape photography using pioneering techniques.

Despite Muybridge's enormous influence on later artists, including Edgar Degas, Cy Twombly, Douglas Gordon and composer Philip Glass, who wrote an opera about him, this autumn Tate Britain will host the first large-scale survey exhibition ever to be devoted to his work. More than 150 works will be on display, some of them never previously shown in the UK.

Much of Muybridge's most famous work was undertaken in the US, but he was born Edward James Muggeridge in Kingston upon Thames in 1830, the son of a grain and coal merchant. He was an almost exact contemporary of the pre-Raphaelites. The family moved to the US in the wake of the 1849 gold rush, and as a young man Muybridge set up as a book dealer in San Francisco.

A serious stagecoach injury in 1860 sent him back to Britain, and little is known of what he did at that time. But when he returned to the States in 1866 he seems already to have been a fully-fledged photographer. Two years later he adopted the first of a handful of name changes, becoming Edward J Muybridge – but he also used the name Helios – Greek for sun.

He began to take some impressive landscape photographs, notably of the extraordinary mountains and forests around the Yosemite valley. Fearless and occasionally unscrupulous, he would forge his way to apparently inaccessible viewpoints (with assistants to help him cart around his 4lb glass plates and other heavy equipment) and even cut down trees to get the best shots. According to Ian Warrell, who is curating the show at Tate Britain, he was an astute marketeer, undercutting the prices of the then dominant photographer of Yosemite, Carleton Watkins; he was also the first photographer to have work published in a guidebook to the valley. In 1871, he undertook a project to document lighthouses on the Pacific coast. The resulting pictures – unearthed in an American archive in 1999 – can be compared to Turner in the grandeur of their compositions.

That same year, aged 41, he married the 21-year-old Flora Shallcross Stone, a photographic retoucher. But in 1874, the year his child Floredo Helios was born, he discovered that Flora was having an affair with a theatre critic, Harry Larkins.

Muybridge shot Larkins dead. During the trial, his dramatic photograph Contemplation Rock, Glacier Point (1872), showing him perched terrifyingly atop a mountain peak, was offered as evidence of his mental fragility, according to Warrell. However, the jury was less interested in that than the argument that "thou shalt not commit adultery" was a more powerful commandment than "thou shalt not kill". Muybridge was thus acquitted, and left for Central America – where he called himself Eduardo Santiago Muybridge.

Flora died in 1875 while Muybridge was taking photographs in Guatemala and Panama, and Floredo was consigned to an orphanage. Returning to the US in 1876, Muybridge began in earnest on his now famous motion studies. Backed by his patron, railroad millionaire and racehorse owner Leland Stanford, he developed the techniques that would allow him to photograph objects in motion – pioneering work at a time when photographs were usually exposed for between two and 10 seconds.

At Stanford's Palo Alto racetrack he developed a technique for photographing horses in motion: he would set up 24 cameras and use a clockwork mechanism to synchronise them, drawing on the technology used to create the telegraph.

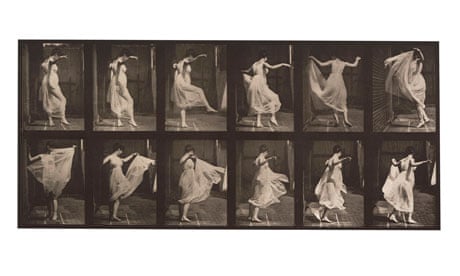

By 1881 he had changed his name for the last time, this time adopting Saxon spelling and becoming Eadweard Muybridge. He began to publish his "motion studies" of horses and humans, also tackling numerous other subjects including wrestling men, fencers, a woman getting in and out of bed, and a dancing woman, and different animals. One series – a naked woman "turning around in surprise and running away" became, argues Warrell, an inspiration for some of Rodin's late sculptures. Others, especially the wrestling men and the dogs, were studied by Francis Bacon and crop up as influences in numerous of his paintings.

Muybridge – a mighty figure with an impressive beard – became something of a celebrity, lecturing at venues including the Royal Institution (where he was introduced by the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII) and animating his photographs using a device he created, called the zoopraxiscope.

He died in Kingston in 1904 just as the cinematic age was dawning – an age that his work had done much to inspire.

Eadweard Muybridge opens at Tate Britain on 8 September.