A great exhibition can sometimes alter one's view of an artist. Morandi: Lines of Poetry, which opens this week at the Estorick Collection in London, is such an event. Apart from a couple of peachy watercolours, everything on show is in stark black and white – the graphic bite of an etching – or the lead-grey of a sharpened pencil.

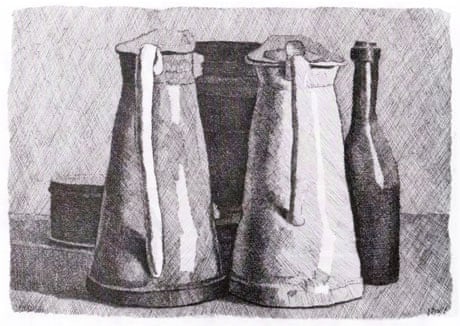

Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964) is not known for his lines. Rather the opposite: in the hazy world of his painted still lifes, everything appears muzzy and soft. The famous objects appearing on the miniature stage of his table – the bottles, bowls, decanters and jugs – do so in something as hazy as limelight. You would not expect to look deep into these masterpieces of 20th-century art and see a sharp edge, an outline or anything as concise as a dot.

So the first revelation of the Estorick show, which brings together more than 80 prints and drawings, is just how strong and decisive they are.

The silver river glittering away into the Italian landscape in a 1929 print is simply a stretch of burning white page defined by black bushes and banks. It's startling, and beautiful, but it might otherwise be quite ordinary without a strange addition. On our side of the river, Morandi has included a tree with its five branches fanning out like the fingers of a hand opening in exclamation at the view; a surrogate admirer.

Up close, the entire image is composed of cross-hatchings so regular and sharp they resemble machine-made stitches, running back and forth across the etching plate at complex angles.

The lines build up in meshes and weaves, steady, patient and strikingly judicious. It's as if he daren't rush it – this is an etching after all, where one false mark can lead to endless problems. But going through the show, you see that Morandi's graphic gifts are so subtle he is able to get over the finest variations of atmosphere, tone and light just through infinitely small variations in the direction of the crosshatchings. It's like a slight change of breeze, shifting the mood and the weather.

And if one knows of Morandi's reputation as a reclusive bachelor who rarely left his native Bologna, living and working in the same shuttered apartment until his death, then this is the second revelation of the show. "Il monaco" – the monk, as one critic called him – who supposedly did nothing but paint, and painted nothing but crockery, clearly ventured out into the world.

There are rushing rapids, quaint old buildings, stands of poplars and elms, a great industrial chimney glowering on the horizon. Morandi becomes fascinated by the nets of a tennis court, turning them into a superfine filigree, and by the stolid flower pots in a neighbour's garden.

There is a fancy cake stand and a kitsch decanter, which (I think) are excluded from the paintings for being too jaunty. There are pale ranunculi that look as though they have been there since the dawn of time, gathering dust in the grey light. There are even, very occasionally, people.

As a young man Morandi tests himself against past art: a Chardin shelf with a basket, vessels and drapes. A hillside in the morning so radiant with light one has the feeling he has been looking at Van Gogh's drawings.

And then, as Morandi approaches his 30s, a characteristically secretive mood steals in. Why is the lid of this tin very slightly open, in a group where all the objects are facing in the same direction, as if it were confiding something about the others in a whisper?

Why are five of the vessels on a table top complete white-outs: incandescent silhouettes plucked from the dark forms behind them as if they were the chosen ones, beamed up by some special magic?

There is a most peculiar divergence in this show. Morandi's pencil drawings become ever more spectral and spare – forms at their most distilled, platonic ideals of bottles and jugs – as the prints grow more complex and dense.

It's as if etching had started out as a parallel medium to painting but the two had in a sense converged. The incised line, the black ink, the white paper: Morandi had discovered that even with these he could evoke chalk-blue tablecloths and hushed afternoons, make objects dissolve into ghostly blurs at dusk.

The prints don't just take Morandi outdoors, they form a journey in themselves. An early still life with a bread basket lacks all charisma, so that one notices how infinitely subtle the arrangement of objects (and the intervals between them) must be to suggest any drama.

Whereas a decade later, in 1931, Morandi's crockery on its table top resembles a city seen across dark water – Manhattan by night, in driving rain. The effect is partly achieved by huddling the massed forms together in shadow, but also by positioning the edge of the table at exactly the right height, so that the darkness below appears elemental.

All his objects have presence. A fantastic convocation of pitchers meets in cabal. Two with their backs against us are hugger-mugger with a third, like tall prelates. A lowly dish, half their height, waits upon their bidding and a bottle that is not part of the secret society cranes its neck to hear. Brilliant white streaks of light shoot down the back-turned pitchers, representing glaze but positively aggressive in their glint. One fears for the bottle.

It is not impossible to make humble objects seem mesmerising and vital: Chardin and Cézanne had this gift, and Morandi learned from them both. But his exacting observations of the world around him – outside as well as in, as this show reveals – produced something altogether new. This is the idea that every relationship in a still life, and even in a landscape, could be psychologically thrilling.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion