At the exit of Les Sablons Metro station, in a well-heeled western suburb of Paris, stands a brown tourist sign that appears to have been misprinted. Next to the recognisable fairground silhouettes of merry-go-rounds and swings, advertising the nearby Jardin d’Acclimatation, is a mess of white blotches. If you screw your eyes up, it looks like a chrysalis, or a strange beetle. This way to the insect house, perhaps?

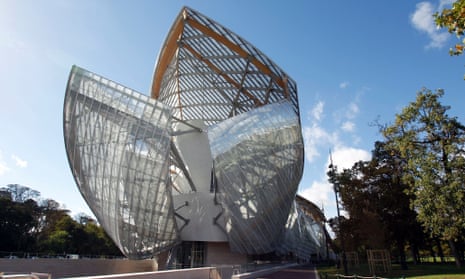

It is, in fact, a sign for the latest building by Frank Gehry – the Fondation Louis Vuitton, which has landed in the woodland park of the Bois de Boulogne as an avalanche of glass sails. Piled up in a staggered heap, these great curved shields twist and turn in the architect’s trademark style, their odd angles poking above the trees, visible for miles around. As if caught in a violent storm, the sails flare open in places to reveal an inner world of white walls, sculpted like whipped meringue, and a dense thicket of steel struts and wooden beams that have been forced into improbable shapes. For an architect often criticised for making “logotecture”, this is one tricky logo to distill – as the tourist board sign-writers have already discovered.

“It is a vessel, a fish, a sailing boat, a cloud,” says Frédéric Migayrou, architecture curator at the Pompidou Centre, who has organised a retrospective of Gehry’s work to coincide with the building’s opening. “It has all the metaphors of smoothness.” Sporting a glittering LV logo at the front door, it could also be a gigantic Louis Vuitton perfume bottle, smashed to smithereens.

Commissioned by Bernard Arnault, head of the LVMH luxury brand empire, whose personal net worth stands at £18.4bn, the complex is a palace for his collection of modern and contemporary art, a corporate cultural showcase. Built on public land, with private funds, it will be given as “a gift to the city” in 55 years’ time. But, like a loud LV handbag a glitzy relative might bring you back from a duty-free splurge, it is a gift the neighbourhood hasn’t seemed all that keen on receiving.

It is a grotesque imposition, in the eyes of some well-to-do local residents, standing as a brash monument to the fact that the country’s richest man can get his own way. Planning codes prohibit building in the protected natural site of the Bois, but structures are allowed under special circumstances, if they reach a height of no more than one-storey. A local campaign saw the project successfully halted in the courts, but then the National Assembly intervened declaring it was “a major work of art for the whole world” and must go ahead. A mysterious sleight of hand with the internal layout, using staggered “mezzanines” around a central atrium, means the building can claim to be just one storey tall – despite rising 50 metres into the air.

In a 2006 documentary on his work, Sketches of Frank Gehry, the architect admitted he gets stage fright when his projects are finished. “I always want to hide under the covers when my buildings open,” he said. “I’m terrified about what people will think.”

Standing in the soaring atrium of the Fondation in front of an army of international journalists, as wayward columns heave to and fro above his head, the 85-year-old architect seems as hesitant as ever.

“It’s very hard to explain how I got here,” he says, looking a bit confused as to what he has made. “When you work intuitively, you can never be sure where you’re going. It’s like the improv jazz musician Wayne Shorter said, when his session musicians asked him what they were going to rehearse: ‘You can’t practice what you ain’t already invented.’”

An exhibition inside one of the museum’s halls goes some way to deciphering the free-form way the building evolved, like every other Gehry project, through ad hoc assemblage, a kind of magpie collage of paper, card, plastic, fabric and other odds and ends. It provides a fascinating window on to the way his office works, with over a hundred models showing the progressive stages of the design, as clusters of boxes come together in a staggered horizontal mass, before being dressed with the billowing costume of nautical sails. Early sketch models show these glassy flaps floating effortlessly above the gallery boxes, while later iterations show the designers wrestling with how on earth these apparently weightless petals will actually be supported.

The answer, in reality, is a hell of a lot of steel columns and glue-laminated timber beams, thrown together in a riotous cat’s cradle of zig-zagging struts and brackets, props and braces. Reaching the summit of the building, where a series of roof terraces spill around the twisting protrusions of the gallery skylights, you are greeted with an eyeful of this stuff, a crazed indulgence of over-engineering – which required the development of 30 technical patents to achieve. It is certainly a spectacle, but it makes you wonder quite what it’s all for.

“It’s for artists to play with,” says Gehry. “Daniel Buren wants to paint stripes all over the sails, and I’m hoping children will do drawings that we can enlarge and hang in the space between the sails and the building. It doesn’t look finished, purposefully, to encourage people to interact with it over time.”

The terraces, he says, are planned to catch particular views – across to the towers of La Defense and Montparnasse, the Eiffel Tower and Montmartre – although it’s hard not to feel the views would be better without the sails and all their struts getting in the way. Still, with the many different stairways charting looping courses around the buffeted white peaks of the galleries, this rooftop landscape will be a kids’ nirvana for hide and seek.

Inside the building, the gallery spaces are curiously straightforward. They comprise a series of voluminous rectangular rooms at the centre of the plan, around which gather the more quirky top-lit spaces, like little side chapels around a grand nave, where Gehry does his wonky thing. There are exhilarating moments, as at the Guggenheim in Bilbao, where spiralling stairs flow on to landings and views are cut through the different volumes, but above all there is an overwhelming feeling of lots and lots of empty space.

In the larger galleries, where lonely films are projected at one end of the gigantic halls, the atmosphere recalls the echoing chambers of the cultural palaces of totalitarian states – muscular monuments to regimes that have precious little to show off. Indeed, of the 11,000 sq m across which the building spreads, just 3,850 sq m are exhibition rooms. The rest is the in-between, free-form Gehry jazz-space. It may be occupied by hanging artwork one day, but for now it feels redundant, the excess fat of a project that had too much money thrown its way.

Reaching for another musical metaphor, Gehry says, “I told the curator: ‘I’ve made you a violin. Now you’ve got to play it.’” But one can’t help thinking that it might have been better for him to tighten the strings and tune it up a little first.

Across town, the Pompidou retrospective provides an illuminating stroll through the entire Gehry oeuvre, stuffed full of models and original sketches, that show you where this brilliant madness all began. It is an interesting way to trace the origins of the Fondation Louis Vuitton, like tracking a complex family tree back to the primal gene pool.

There are some wonderful things, like Gehry’s original drawings of his own house in Santa Monica, the building that signalled the beginnings of his “ad hocist” approach with brazen flair in 1978. A suburban bungalow, around which he constructed an alternate universe of corrugated tin and chain-link fencing, it began a series of private house commissions that revelled in deconstructing the Los Angeles vernacular and breaking the conventional rules of how things are made.

There are houses that achieve special feats with cheap materials, cutting holes through the stucco to reveal the timber framing, shifting rooms off-axis to open up surprising views, their plans carefully crafted to create dynamic spatial relationships – without the need for undulating titanium.

Arranged by decade, it is easy to see how Gehry’s preoccupations drift, from these early experiments that make witty references and play on the history of building, towards a more supple sculptural language that is entirely of his own making, and which begins to reference nothing but itself.

The key turning point comes with the barely believable saga of the Lewis residence, an 11-year project to make a gargantuan play-mansion for insurance magnate Peter B Lewis, which never got built. The design begins in 1984, as a cluster of rooms on a waterside site, drawing on the organisational logic of some of Gehry’s previous villas. As the years go by, the ambition grows, until the project has inflated into a bizarre extravaganza of frenzied form-making, with wiggling canopies next to lumpy termite mounds, horses’ heads lying alongside metallic fish, as if a futuristic toy box had been emptied out across the site.

“I told him to just carry on designing and keep sending me the bills,” says Lewis in an accompanying film, disclosing that by 1995, Gehry’s fees alone had reached $6m, for a house that would have cost $82m to build. “It was just too much. By then my lifestyle had changed, and I no longer wanted to throw these big parties. I realised I was building a museum.”

Lewis’s loss was Bilbao’s gain. His munificent patronage allowed Gehry to develop the technical tools and computer know-how that he would go on to employ on the Guggenheim Museum, and countless other projects since then. But it should also have been a useful lesson for the architect, and a cautionary tale: that budgets can be too big, clients too sloppy and briefs too vague – and that it’s important to know when to stop.

- Fondation Louis Vuitton opens to the public on 27 October. Frank Gehry is on show at the Pompidou Centre until 26 January 2015.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion