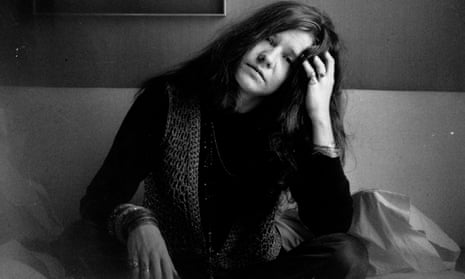

An evening at the Royal Garden Hotel in April, 18 months ago. I was meeting Janis Joplin. I fished around for a while, trying to get replies from her. She was rude. Then I suddenly realised what was difficult to believe. The biggest female name in rock – which is what she was, then – had stage fright.

I asked her why. She said that it was easy, in America, to make people believe that she was a blues singer. She said that reputations came cheap there. In England, for years, she said, authentic blues had been sustained by an audience that really understood blues. And she was, for the first time, waiting to sing, across the road, at the Albert Hall, for an audience she feared because she trusted them: and so she doubted her own ability. “It’s like your very first date,” she said. “The very first one. You understand? No, you don’t.”

The next evening, I understand. After her first album, “Big Brother and the Holding Company,” she got caught up in an image machine that hurt more than we knew at the time “Cheap Thrills,” the first album to star her as a solo artist, was received here as an overblown piece of work. Around Christmas, 1968, it had been chic to play “Ball and Chain,” the featured track. It seemed to me to meander purposelessly. She made mincemeat of the music.

On stage, at the Albert Hall, she appeared tiny in the spotlight, wearing an electric blue jumpsuit. All at once, she tried to gather all of her audience inside herself, settling for nothing less: squeezing her voice dry, her arms pumping, her hands in fists. She stumbled back from the microphone, as if at the rate of her and her band’s own decibel volume. Then, somehow, and there’s no way to explain how it was achieved, the sound focused, and pointed down the auditorium like a locomotive, directed at and then into us in the audience. That is what couldn’t be heard on record.

Yes, there is a comparison between Janis Joplin, whose death was announced yesterday, and Jimi Hendrix, but not the one that may be made by other commentators. The question now is: how much of themselves can rock musicians give in their music, to their audience, and survive? “Rolling Stone” magazine, a while ago, labelled a feature on Janis Joplin “The Judy Garland of Rock.” That headline is rather dreadful, now. Janis knew what she was doing, at the Albert Hall, and at all her other concerts. She was demanding too much. I’d like, now, to have settled for less.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion