It is one of the most famous music photographs in history. Images this iconic usually first appeared on the covers of albums or magazines. This one graced neither. When it first became notorious, the picture was nearly twenty years old and, to this day, most people don’t know just how it happened. When I first searched for an outtake online and couldn’t find one, I assumed it was a one-off. When I finally found snapshots taken just milliseconds before, I couldn’t believe that no one had posted them online. I didn’t want to share what I’d found until all of my questions about the famous finger were answered. Two years later, they’re still not. Glad to see there’s still some mystery in the world…

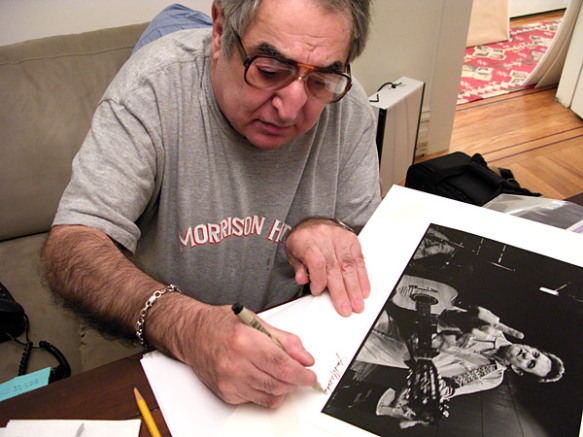

Jim Marshall started taking photographs of musicians in the 1950’s with one John Coltrane and was quickly in demand by every major record label imaginable, eventually shooting more than 500 album covers. He was hired by the Beatles to document their very last concert in 1966 and took some of the most well-known pictures at the Monterey Pop Festival, Woodstock and countless other historic events. He’s considered by many to be the first real rock photographer and possibly the greatest ever.

Marshall first met singer Johnny Cash in 1962 at a Greenwich Village cafe when he was introduced by another regular subject of his, Bob Dylan. When the two hit it off, so began a 30 year relationship, visually collected in the 2010 Chronicle Books release, Pocket Cash. Marshall had already photographed Cash at several folk festivals when, at Johnny’s insistence, he was hired by Columbia Records to photograph the recording of the famed At Folsom Prison album in 1968. The idea of recording a concert at a prison had been kicking around for years and, with shake-ups at Columbia, Cash finally had a supporter of the project in producer Bob Johnston.

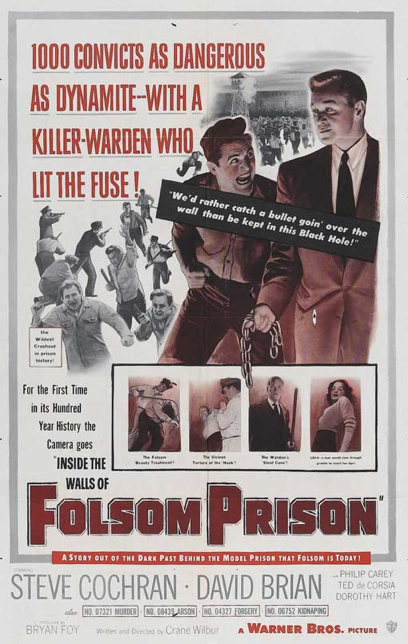

The Man In Black is synonymous with prisons thanks to his first big hit, “Folsom Prison Blues”, though he never actually served a prison sentence. Cash was arrested seven times and spent a few nights in jail but he wrote extensively on his empathy for prisoners and how close he always felt to them. Those feelings may have began while he was serving in the U.S. Army in West Germany in the early 1950’s and his platoon watched the 1951 film Inside The Walls Of Folsom Prison. It inspired him to pen the song that would hit #1 on the country charts in 1955. He began to get deeply personal letters from inmates and invitations from jails all over the United States. Cash’s prison first performance took place in Huntville, Texas in 1956 and he played them regularly throughout his career.

The Man In Black is synonymous with prisons thanks to his first big hit, “Folsom Prison Blues”, though he never actually served a prison sentence. Cash was arrested seven times and spent a few nights in jail but he wrote extensively on his empathy for prisoners and how close he always felt to them. Those feelings may have began while he was serving in the U.S. Army in West Germany in the early 1950’s and his platoon watched the 1951 film Inside The Walls Of Folsom Prison. It inspired him to pen the song that would hit #1 on the country charts in 1955. He began to get deeply personal letters from inmates and invitations from jails all over the United States. Cash’s prison first performance took place in Huntville, Texas in 1956 and he played them regularly throughout his career.

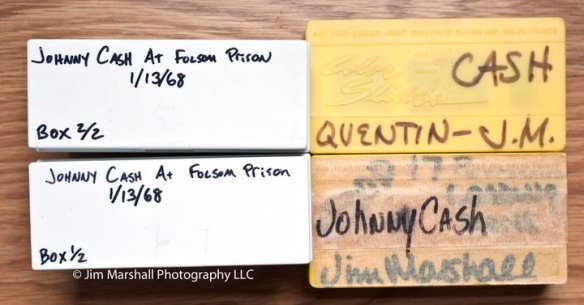

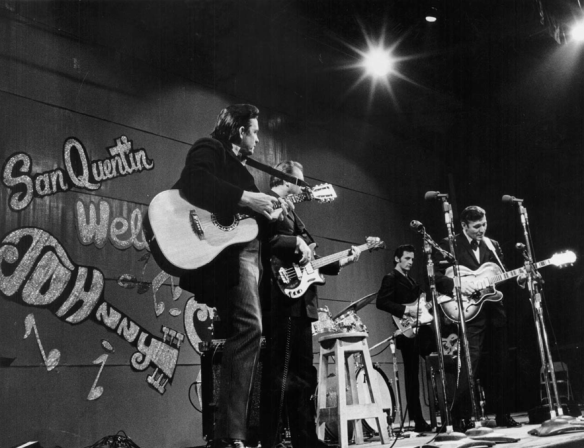

Though now it seems like a no-brainer to record an outlaw country legend like Johnny Cash in a room full of prisoners, Columbia Records was taking a huge chance on something that had never been done before. Cash had only recently cleaned up after years of erratic drug-and-alcohol fueled behavior. With it being the namesake of Cash’s biggest hit, Folsom Prison in northern California seemed an obvious choice to host the recording, but the label also pitched the idea to the state’s largest facility, San Quentin State Prison. Cash had played Folsom in 1966 and they responded first, so the album was recorded there on January 13, 1968. The gamble paid off. The record went to #1 in the country charts, #12 on the pop album chart, was universally hailed as an unforgettable recording and revived Cash’s career.

Though now it seems like a no-brainer to record an outlaw country legend like Johnny Cash in a room full of prisoners, Columbia Records was taking a huge chance on something that had never been done before. Cash had only recently cleaned up after years of erratic drug-and-alcohol fueled behavior. With it being the namesake of Cash’s biggest hit, Folsom Prison in northern California seemed an obvious choice to host the recording, but the label also pitched the idea to the state’s largest facility, San Quentin State Prison. Cash had played Folsom in 1966 and they responded first, so the album was recorded there on January 13, 1968. The gamble paid off. The record went to #1 in the country charts, #12 on the pop album chart, was universally hailed as an unforgettable recording and revived Cash’s career.

After the success of Folsom, Columbia Records released the compilation album Heart Of Cash and, in early 1969, they put out Cash’s new LP, The Holy Land, which mostly contained religiously themed songs. It was a far cry from the rawness of performing in a room full of criminals but the album went to #6 on the country charts and the Carl Perkins-penned single “Daddy Sang Bass” was a huge hit, staying atop the country charts for six weeks. With the public eager for more jailhouse rock, it was no huge surprise that Cash did another live record next. This time they went just a little over 100 miles southwest of Folsom to San Quentin State Prison, across the Bay from the famous Alcatraz Prison. Cash had already played there three times before, including New Years Day 1958.

Once again, Marshall was asked to take photographs for the album and England’s Granda Television arranged to film the concert for a BBC documentary. On February 24th, 1969 they arrived at the prison early to set up for the show. Because it was being filmed by a full camera crew at quite an expense, the producers wanted to make sure they got what they needed. Cash was obviously fed up with the demands of the Brits, his label and the prison. Before he played “I Walk The Line”, he told the inmates, “They said, ‘You gotta do this song, you gotta that song. You know, you gotta stand like this or act like this.’ I just don’t get it, man. You know, I’m here to do what YOU want me to and what I want to do.” His specially-penned ode “San Quentin” was so scathing and the prisoners loved it so much that he played it twice in a row. Time and time again, he said the very things he was asked not to and did it with a grin because he knew he could get away with it. The prisoners couldn’t but he was an invited guest….with a microphone.

Like its predecessor, San Quentin was a huge success, even bigger than Folsom, in fact. While the album and his version of Shel Silverstein’s “A Boy Named Sue” topped the country album and single charts, they also became crossover pop hits. The LP topped the pop album charts for five weeks in the fall of 1969 and won the Grammy for Album of the Year while “Sue” went to #2 in Billboard’s pop singles charts. Over time, the album recorded at Folsom has become the more famous of the two, probably thanks to its namesake hit. Both albums reached the three million dollar mark in sales in 2003.

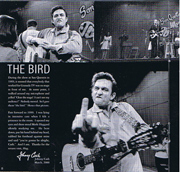

In 2000, when Columbia released the full San Quentin show on cd, the liner notes included an essay by singer Marty Stuart, recollections by Cash’s wife June Carter Cash and Stuart’s interview with one-time San Quentin inmate Merle Haggard. Haggard was so inspired by Cash’s performance, that he let his fellow inmates convince him to ditch an escape plan to pursue a singing career. Johnny Cash’s own two paragraph contribution is titled “The Bird”. In it, he explains that during the show, the camera crew was onstage blocking the inmates’ view. “At some point,” he explains “I walked around my microphone and yelled ‘Clear the stage! I can’t see my audience!’ Nobody moved. So I gave them ‘the bird’. Hence the picture.” Included is a shot that looks like it was taken just before the finger came out. Cash is already forming the famous “F”, biting his lower lip. It’s a great story but Johnny remembered it wrong. He’s not the only one.

In 2000, when Columbia released the full San Quentin show on cd, the liner notes included an essay by singer Marty Stuart, recollections by Cash’s wife June Carter Cash and Stuart’s interview with one-time San Quentin inmate Merle Haggard. Haggard was so inspired by Cash’s performance, that he let his fellow inmates convince him to ditch an escape plan to pursue a singing career. Johnny Cash’s own two paragraph contribution is titled “The Bird”. In it, he explains that during the show, the camera crew was onstage blocking the inmates’ view. “At some point,” he explains “I walked around my microphone and yelled ‘Clear the stage! I can’t see my audience!’ Nobody moved. So I gave them ‘the bird’. Hence the picture.” Included is a shot that looks like it was taken just before the finger came out. Cash is already forming the famous “F”, biting his lower lip. It’s a great story but Johnny remembered it wrong. He’s not the only one.

When I first started to look for other photos taken that day, all I could find were a few shots of the band performing in dark suits. I’d never looked that closely at the backlit Man In Black on the cover of the LP but noticed that he wasn’t wearing the same outfit as he is in the finger shot. I finally found that Marshall’s famous picture was actually taken at a rehearsal earlier in the day while Cash was wearing a prison jumpsuit that was auctioned off in 2010. Julien’s Auctions expected to get $3000-$5000 for it. It went for $50,000.

According to Marshall, they didn’t even use one of his photographs for the cover, though it’s often credited to him. It seems strange that they would hire a well-known photographer like Marshall and not use his shot for the cover. Marshall dismissed it as “more stylized”. They did use twelve smaller color photographs of his for the back cover, including one reversed shot so Cash looks like he’s playing his guitar left handed. The original liner notes credited one Henry Fox with the cover shot but there is no information to be found on him. In fact, if you search for “Henry Fox photographer” online, time and time again, you find information on 19th century British inventor Henry Fox Talbot, who is credited with the development of the photographic process. I had to wonder if maybe it was Marshall using a pseudonym for some reason. In the 2000 Columbia album reissue, which has many extra shots not on the original release, it solely credits Marshall with the album’s photography.

According to Marshall, they didn’t even use one of his photographs for the cover, though it’s often credited to him. It seems strange that they would hire a well-known photographer like Marshall and not use his shot for the cover. Marshall dismissed it as “more stylized”. They did use twelve smaller color photographs of his for the back cover, including one reversed shot so Cash looks like he’s playing his guitar left handed. The original liner notes credited one Henry Fox with the cover shot but there is no information to be found on him. In fact, if you search for “Henry Fox photographer” online, time and time again, you find information on 19th century British inventor Henry Fox Talbot, who is credited with the development of the photographic process. I had to wonder if maybe it was Marshall using a pseudonym for some reason. In the 2000 Columbia album reissue, which has many extra shots not on the original release, it solely credits Marshall with the album’s photography.

Not surprisingly, the middle finger shot was not used as part of the album’s artwork when it was released on June 4, 1969, less than four months after it was recorded. It’s hard to imagine that the rehearsal photo was ever NOT famous but it actually remained almost completely unseen for nearly 20 years. It was shown on occasion at Jim Marshall photography shows but very few prints were made. Somehow, posters and t-shirts with the photograph started to show up in record stores in the 1980’s. Marshall often called it “the most ripped off photograph of all-time”.

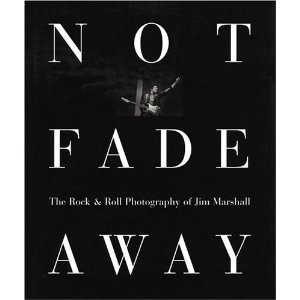

The first book of Marshall’s photography, Not Fade Away, was published in 1997 and the Cash photo was included. Thirteen years later, word spread on music websites that he had finally revealed the secret behind the photo but in the book, Marshall offered this explanation:

The first book of Marshall’s photography, Not Fade Away, was published in 1997 and the Cash photo was included. Thirteen years later, word spread on music websites that he had finally revealed the secret behind the photo but in the book, Marshall offered this explanation:

“I forget why he flipped the bird in this picture, it might have been directed at the television crew who was filming there, or I might have suggested doing a special shot for the warden, but for whatever reason, this has become a very famous, iconic picture”

Before this came to light, people often assumed that Cash was frustrated with whoever was taking the picture. He’s definitely looking right at the cameraman but giving Jim Marshall the finger was nothing new, even in 1969. Marshall is a famous self-proclaimed hard-ass who loved guns but he was adored by his subjects, which is why he got such personal expressive shots of them. That’s why Cash asked him to shoot at both Folsom and San Quentin. “It shows John’s individuality,” Marshall noted on his own website, “but the gesture was definitely done in jest. John’s got a great sense of humor and this was not a serious shot.”

Cash downplayed the dangerous nature of the photo, noting that his mother-in-law is standing behind him and he’s got a wedding ring on the next finger over. The Man In Black was an outlaw country legend, adored by prisoners worldwide but he was also a religious man constantly battling his demons. It’s these contrasts that make Marshall’s shot such an interesting image and made Cash such an interesting man. Marshall knowing about his desire to do the right thing probably helped the photo stay unseen for so long. Bill Miller, close friend of Johnny Cash and founder of JohnnyCash.com and Johnny Cash Radio said, “I can tell you that Johnny did not like the photo and disliked signing them even more.”

Johnny Cash was arrested in October 1965 when U.S. Customs agents found hundreds of pep pills and tranquilizers in his luggage. The Man in Black–who was returning by plane from a trip to Juarez, Mexico–spent a night in the El Paso jail, and later pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor count. Cash paid a $1000 fine and received a 30-day suspended sentence. Photo from TheSmokingGun.com

When the photo finally appeared in Marshall’s book in 1997, Cash’s career was on a huge upswing, thanks to a series of records produced by Rick Rubin, who’d previously been known for working with acts like Beastie Boys and Slayer. Their first album together, 1994’s American Recordings, was the quietest album Cash had ever made, done with just him and his acoustic guitar and recorded in Rubin’s living room. The album was a huge success and won a Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Performance. Suddenly, he was playing to thousands of young alternative-nation citizens at places like England’s Glastonbury Festival and doing a guest spot as a coyote on The Simpsons. It was such a pleasant surprise to Cash, that he agreed to do something different for the second record he did with Rubin, 1996’s Unchained.

Before American Recordings, Cash was reluctant to make a record that deliberately appealed to Gen X’ers. Rubin assured him that he wanted to do it Johnny’s way and they’d see how it went. Maybe it was his intention all along to make something like Unchained but once Cash was open to suggestion, the floodgates opened. Having Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers as the backing band for the album kept it in the country-rock world but now he was singing songs by Beck and Soundgarden with Flea on bass. If the Lollapaloozers liked him before, now they LOVED him.

For years, Cash had been ignored by modern country radio. An album as stark as American Recordings would’ve sounded completely out-of-place next to the slick, young stars of the day but Unchained had a full sold country-rock band behind him. Still, the record got no love from American country radio stations and no nominations at that year’s Country Music Awards. The Grammy voters from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, however, have had a long history of favoring veteran artists, like when Jethro Tull famously beat Metallica in the first ever Hard Rock/Metal category. Sure enough, Unchained was nominated for two 1998 Grammys: Best Male Vocal Performance for “Rusty Cage” (which went to VInce Gill’s “Pretty Little Adrianna“) and Best Country Album, which Cash won, beating out Alan Jackson, Patty Loveless, George Strait and Dwight Yoakam. The album category was added in 1965 and was won back-to-back years by Roger Miller but then done away with until 1995, making Cash only the fifth singer to win the award.

Although it had been a long while between trips to the podium, Cash’s trophy case was hardly empty. Between 1968 and 1971, he won six Grammys (including awards for liner notes he wrote for At Folsom Prison and Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline) and six Country Music Awards (including five in 1969 after the success of San Quentin). Although he received a spoken word Grammy for being part of 1987’s “Interviews from the Class of 55 Recording Sessions” and a Grammy Legend award in 1990, 24 years had passed since Cash had received a Grammy for a new recording. In all, he received 18 Grammys, including six for his work with Rubin.

It’s standard practice for record labels to take out ads congratulating their Grammy-winning artists in Billboard Magazine, which has been the bible of the biz for over 100 years. Warner Brothers took out an ad congratulating all the 1998 winners on record labels under their umbrella, including Best New Artist winner Paula Cole who caught heat for flipping a bird during her performance, though it barely managed not to end up on camera. Since Warners owned American Records, the ad also included Cash but Rubin had an idea that was straight out of Cash’s very own playbook.

In 1964, Cash had immersed himself in the history of the United States’ treatment of American Indians. He recorded an entire album of songs on the subject, called Bitter Tears. The lead single chosen was “The Ballad of Ira Hayes”, the tale of a Pima Indian war hero who was immortalized in the famed Iwo Jima photograph but had died a penniless alcoholic. Without support from radio stations or his own record label, it went nowhere. An editor at a country music magazine insisted Cash should resign from the Country Music Association because “you and your crowd are just too intelligent to associate with plain country folks, country artists and country DJs.” In response, Cash wrote an open letter to the music business and had it placed as a full-page ad in Billboard which ran on August 22, 1964. The letter explained his motivation for writing the song and then he addressed the hit-makers. Some highlights:

“D.J.’s — station managers — owners, etc.,

Where are your guts?” I think you do have guts – that you believe something deep down (And pardon the dialect – mine is one of 500 or more in this land). Still actual sales on Ira Hayes are double the ‘Big Country Hit’ sales average. Classify me, categorize me, STIFLE me-but it won’t work. These lyrics take us back to the truth. You’re right! Teenage girls and Beatle record buyers don’t want to hear this sad story of Ira Hayes but who cries more easily and who goes to see sad movies to cry??? Teenage girls. Yes I cut records to try for ‘sales’. Another word we could use is success. Regardless of the trade charts — the categorizing, classifying and restrictions of air play, this not a country song, not as it is being sold. It is a fine reason though for the gutless to give it a thumbs down. ‘Ira Hayes’ is strong medicine. So is Rochester, Harlem, Birmingham and Vietnam. But as an American who is almost a half-breed Cherokee-Mohawk (and who knows what else?), I had to fight back when I realized that so many stations are afraid of Ira Hayes. Just one question: WHY???

NOBODY BUT NOBODY MORE ORIGINAL THAN JOHNNY CASH”

It worked. The song went to #3 in the country charts. Likely knowing about Cash’s love of public showbiz shaming and having recently seen the finger photo, Rick Rubin suggested they take out an ad in Billboard “thanking” the country music world with Jim Marshall’s photo. In the Country Music Television documentary Johnny Cash vs Music Row, Rubin talked about how the $20,000 ad came about.

“When I first suggested it, he just laughed and said, “Great.” He said, “I’m not going to tell you to do it but I’m certainly not going to tell you not to do it.” and actually Johnny and I wrote it together. We went back and forth. I remember he wanted it to say “music establishment” as opposed to just country radio. We talked about it. We talked about it a lot.

From the Unearthed liner notes:

From the Unearthed liner notes:

“The ad struck a resonant chord with Johnny’s fellow musicians. Like the 1969 San Quentin prison concert where the “bird” photo came from, it was the perfect gesture of defiance, of an individual squaring up to the establishment and its arbitrary, hard-hearted rules. Suddenly, the American offices were deluged with requests for copies of the ad from artists, most of whom bristled at their treatment by the music industry. It got to the point where American had posters made of it, because every day another musician or recording studio would call up with a request. (Ironically, even executives at Warner Brothers Records proudly displayed framed copes of the ad in their offices). And Willie Nelson posted it in his tour bus, with no end of travelling bands following his lead.”

George Jones told USA Today that he laughed out loud when he saw the ad and threatened to run one for his next single filled with baseballs, footballs and basketballs with the caption “If radio had any, they’d play this record.” Some industry leaders backpedaled publicly. WSM-FM in Nashville offered to broadcast a live Johnny Cash concert but Radio & Records music editor Steve Wonsiewicz responded that “if there was a huge demand for their music, it would get played.” While the ad did get its fair share of press at the time, it was mostly within music business circles that it became legendary. Billboard is a trade magazine, so a lot of the general public never heard about the stunt in 1998 and even fewer today know that it was the advertisement that first made the photo famous.

Through Yer Doin’ Great, finding and sharing outtakes of famous photos has become a fun passion. Once I started posting these shots, there were two that I wanted to find most: the cover of the Clash’s London Calling and the prison shot of Johnny Cash. I finally came across a Clash songbook that had another shot of Paul Simonon’s famed bass-smashing but the San Quentin shot eluded me. I’d look for it every so often but could barely find any shots taken that day, let alone a few seconds before or after. I figured that because it was taken in the pre-digital days where every shot counted and film wasn’t free, that maybe there were no extra images of those moments.

I kept finding interesting details but often found well-respected, official sites getting the date, location and other facts wrong (usually placing it at Folsom Prison from the year before). I figured that if I couldn’t find an outtake, I’d at least try to tell the tale and get it right. It’s too good of a story not to share. Then, I accidentally came across a page on the official Jim Marshall Photography website late one night about his 2004 book Proof. The page even had a Johnny Cash prison contact sheet but it was from the Folsom concert. A few clicks later, I found a description of the book that mentioned the “bird” photo among other highlights. I couldn’t order a copy fast enough. Marshall’s website linked to Amazon, which showed that it was out-of-print but finding a used copy only took a few extra minutes. Thanks again, internet.

I kept finding interesting details but often found well-respected, official sites getting the date, location and other facts wrong (usually placing it at Folsom Prison from the year before). I figured that if I couldn’t find an outtake, I’d at least try to tell the tale and get it right. It’s too good of a story not to share. Then, I accidentally came across a page on the official Jim Marshall Photography website late one night about his 2004 book Proof. The page even had a Johnny Cash prison contact sheet but it was from the Folsom concert. A few clicks later, I found a description of the book that mentioned the “bird” photo among other highlights. I couldn’t order a copy fast enough. Marshall’s website linked to Amazon, which showed that it was out-of-print but finding a used copy only took a few extra minutes. Thanks again, internet.

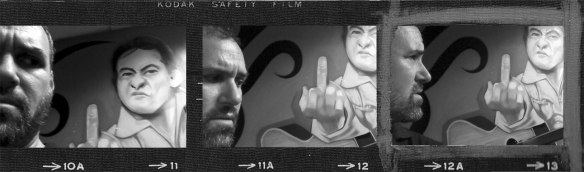

When it arrived a few days later, it turned out to be a library copy from Centerville, Ohio. I thumbed through a dozen famous photos before coming to the pages featuring San Quentin. On the right page was the famous shot, with a short caption and a mention of doing the shot for the warden. On the left page is the proof sheet with 34 black and white shots taken from before the concert. Other than five shots of Johnny sitting at a table talking to the Granada Televsion staff, the roll is full of fairly uneventful shots of the band rehearsing in prison jumpsuits. Noticeably absent is the shot used in the 2000 reissue I thought was taken just before. Looks like Cash told Marshall to eff off more than once that day. Maybe he told the BBC crew too.

Two shots into the rehearsal, Marshall captured a bit of fun that would become his most famous shot. He snapped three frames of Johnny flipping the bird. The third shot was marked with a blue grease pen and destined to go down in history. In Jim Marshall’s book Pocket Cash, he recalled “Three frames, a 21-millimeter lens. I don’t know if the film crew caught it. Elton John bought all three frames.” Holding that ten year old book, it felt like me and Elton were the only two people in the world who knew or cared about all three pictures. I almost shared them that night but wanted to get the story right before I did. Two years later, here we are.

After all of these years, interest in Cash’s prison concerts is still huge. Just last week, new unseen Jim Marshall photos from San Quentin became available at Sonic Editions and everyone from Esquire to Dangerous Minds shared the good news. Still, the mystery remains whether the finger was for the BBC or the warden. When author Jonathan Silverman asked Marshall about it in 2004, he said “It was some of each. It was thirty five years ago. I don’t fucking remember.” Marshall died on March 23, 2010 in his sleep in New York.

Johnny Cash continued to record with Rick Rubin despite a variety of illnesses, releasing two more albums for the American series and recording enough to fill two more posthumously before he passed away on September 12, 2003. His accomplishments are legendary. He was inducted into both the Country and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, was the oldest artist to be nominated for an MTV Video Music Award, received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1996 and ruined the middle finger for the rest of us. As obscenity has become less scandalous over time, the gesture is now pretty tame but Jim Marshall’s photograph still speaks volumes about danger, attitude, individuality and biting the hand that feeds. Giving that salute at a time when morality was so different and doing it under the intense scrutiny of a maximum security prison is something no one will ever touch.

C’mon, you really think that even the most dangerous criminal in this day and age putting up their finger has half of the power as that picture? Fuck you.

A FEW MORE SOURCES & WORTHWHILE FINGERS

THE OFFICIAL WEBSITE OF JIM MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHY

JOHNNYCASH.COM

JOHNNY CASH MUSEUM in Nashville

THE BIRD, THE FINGER, THE LEGEND. The Selvedge Yard’s collection of historic middle finger photos

THIS LAND IS THEIR LAND The Bluegrass Special’s piece on In A Heartbeat and a Guitar: Johnny Cash and the Making of Bitter Tears by Antonino D’Ambrosio

THE BITTER TEARS OF JOHNNY CASH from Salon.com

JOHNNY CASH LIVE AT SAN QUENTIN PRX’s hourlong audio story on the concert, other PRX specials on Johnny Cash available here

NINE CHOICES: AMERICAN CULTURE AND JOHNNY CASH by Jonathan Silverman

JOHNNY CASH INFO CENTER

JOHNNY CASH’S MIDDLE FINGER FACEBOOK GROUP

SAVING COUNTRY MUSIC

CASH’D OUT World’s greatest Johnny Cash tribute act, straight outta San Diego

“GRANDPA GEEZER” JOINS CASH’D OUT AS JUNE CARTER

BASTARD SONS OF JOHNNY CASH Another band with San Diego ties that tips their hat to Johnny

MORE FAMOUS ROCK/ROLL IMAGE OUTTAKES at Yer Doin’ Great’s Facebook page

We don’t post much here but there’s always something happening at Yer Doin’ Great’s Facebook page so please give us a “like” and follow along.

Pingback: Yer Weekend Chuckle: A “Thanks” for the Ages : This ain't Hell, but you can see it from here