At 10 years old Kengo Kuma decided he wanted to become an architect when his father took him to see the Yoyogi National Gymnasium by Kenzo Tange. By the time he reached college he traveled to search for something to replace the predominant building materials concrete and steel. After visiting sun-dried brick houses in the Sahara and modest wooden houses on Japanese islands, he became convinced that the age of large tall buildings had come to an end, in place for small- scale architecture informed by rural villages.

In the 90s during the Japanese economic downturn Kuma had the chance to work on small buildings in the countryside. Working with local craftsmen he noticed the stark contrast between them and the building managers in Tokyo who were only interested in financial factors and building schedules. To the construction company buildings consisted of money and time. Kuma traveled Japan to find craftsmen who had not given up and continued to hone their craft. From them he learned about natural materials like wood, paper and earth. Things, according to Kuma, they do not teach in school.

His expanding practice allowed him to work in the Chinese countryside, Europe and the US. These experiences taught Kuma countries had less meaning for him than making things using local materials and skills that are unique to that place. He came to the conclusion that he should work closely with craftsmen in each location and forget about the country.

Kuma feels modernism that depended on concrete, steel and glass, resulted in a severing of the connection between humans and nature. Traditional Japanese architecture uses soft and light materials like wood and paper that provide a more gentle connection between people and nature. The skills to use these materials were honed over centuries. Kuma thinks this architecture is full of hints about how we can reconnect with nature and maybe even solve environmental problems that the world is currently facing.

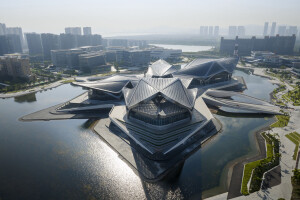

1. Odunpazari Modern Art Museum, Odunpazari, Turkey, Japan, 2019

Informed by Ottoman wooden houses and the location’s former function as wood trading market, Kuma shaped the Odunpazari Modern Art Museum as stacked and interlocking boxes in varying sizes. The size of the boxes relates to the surrounding houses, yet the accumulation of them signifies a larger cultural institute.

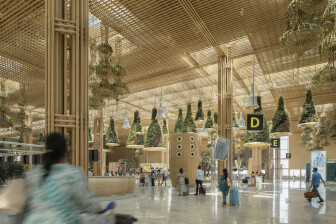

2. V&A Dundee, Dundee, Scotland, UK, 2018

The V&A Dundee proposes an integrated way of achieving harmony between museum and environment. Referencing the beautiful cliffs of Scotland, multiple layers of precast concrete that run horizontally around the curving facade attempts to translate this geographical uniqueness into an artificial cliff. Creating patterns of shadow that change with weather over time. Inside, the foyer uses locally available wood together with exposed concrete and architectural mesh to create soft textures and the feeling of an urban ‘Living Room.’

3. Portland Japanese Garden, Portland, US, 2017

Considered to be one of the most authentic Japanese Gardens outside of Japan, architect Kengo Kuma completed an expansion of the existing garden which first opened in 1967. The three volumes, a Village House, Garden House and Tea House, are arranged like a small village with pagoda inspired green roofs.

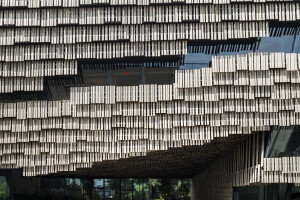

4. China Academy of Arts’ Folk Art Museum, Hangzhou, China, 2015

Located on the hillside of a former tea field, Kuma wanted the building to reflect the ups and downs of the slope. The volumes react to the topography with small individual roofs that look like a small village. The facade is covered with a screen of tiles hung up by stainless steel wires. The discarded tiles were sourced from local houses.

5. Daiwa Ubiquitous Computing Research Building, Bunkyo, Japan, 2014

The cedar clad exterior is inspired by fish scales. The high-tech facility is contrastingly built with a more traditional mud wall, built by a local craftsman. Kuma intended to design a soft building made of wood and earth. An organ-like volume wrapped in a soft membrane.

6. Asakusa Culture Tourist Information Center, Tokyo, Japan, 2012

Kuma approached the Asakusa Culture Tourist Information Center tower like a stack of one-story houses. The technical program is placed in diagonally shaped layers in between relatively high levels. The angular ceiling and roofs differ from floor to floor to give the feeling of a vertical village.

7. Starbucks Dazaifu, Fukuoka, Japan, 2011

Located in the main street towards Dazaifu Tenmangu, an important tourist attraction, Kuma created a configuration of 2000 cedar sticks joined together in groups of four. Kuma refers back to the traditional Japanese technique of piling up small parts to assemble a larger structure.

8. Yusuhara Wooden Bridge Museum, Kochi, Japan, 2010

The Wooden Bridge Museum is a perfect example of how Kuma translates Japanese traditional architecture into a contemporary building. In the same way like Starbucks Dazaifu the building is a structural system composed out of small parts. The beautifully connected system called ‘tokiyo’ allows for a large-span laminated wood cantilever without having to rely on large structural elements.

9. Yusuhara Community Market, Kochi, Japan, 2010

Yusuhara is a small town with 3900 inhabitants in the mountains located on the island of Shikoku. Learning from local traditions Kuma used thatching as exterior walls. The thatched elements can be rotated to provide ventilation. For the interiors of the market Kuma used rough cedar logs. The architect tried to create a new type of architectural language for Yusuhara using raw textured materials.

10. GC Prostho Museum Research Center, Kasugai-shi, Japan, 2010

Inspired by an old Japanese toy called ‘cidori’, Kuma used a spatial configuration of sticks for the GC Prostho Museum Research Center. A museum and research center for a dental care manufacturer. The joints were realized without having to use glue. Kuma likened the idea that someone could build this kind of structure with their own hands using clever joinery.

Kuma - Complete Works 1988-Today will be available from July 11 in the Taschen webstore and September 6 on Amazon.