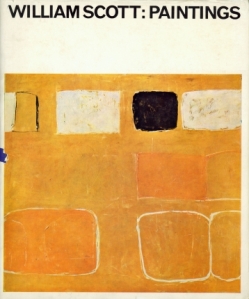

Lund Humphries Landmarks – William Scott: Paintings, edited and introduced by Alan Bowness, with contributions from Michel Ragon and Werner Schmalenbach (1964)

Frances Spalding discusses the modern ‘cool’ of Lund Humphries’ 1960s monograph on William Scott and reflects on the cementing of the artist’s style in the preceding decade.

This monograph followed the format laid down by the first Lund Humphries monograph in 1944, but its style belongs very definitely to the 1960s. The typeface chosen is throughout sans-serif, and the general layout is cool and spacious. There are 23 colour illustrations and 126 black-and-white, and, surprisingly, it is the latter that make this book a sumptuous treat and, today, a collector’s item. Norbert Lynton once claimed that William Scott was a master of tonal painting, adding ‘perhaps the best here since Whistler’. These superb black-and-white reproductions perfectly uphold this claim. They are especially effective in communicating the boldness and command of Scott’s abstracts painted between 1952 and 1954.

What terminated this first abstract period, as is nowadays well known, was the reaction Scott experienced in the wake of a three-month visit to the States in 1953. He taught at a summer school at Banff, Alberta, then visited New York and Long Island, meeting Pollock, Kline, Rothko and de Kooning. Alan Bowness’s summary explanation in this monograph reads as follows: ‘The size and impact of American painting overwhelmed him: it had a directness and immediacy that he sought in his own painting. But its “public”, “open” quality did not appeal to him, and though he could admire their work, he felt no desire to imitate the Americans. Indeed the New York visit confirmed Scott’s sense of being a European artist.’

What puzzles me here is that ‘directness and immediacy’ – the qualities which Scott appreciated in painting – are closely related to the ‘public, open quality’ which he abjured. So what exactly was it that he disliked? And what needed to remain private, closed, concealed? As Bowness’s conclusion suggests, Scott clearly experienced a crisis of identity after his first-hand experience of American Abstract Expressionism, and his response, as a painter, was to turn back to the nude and the still-life. But out of this ‘wobble’ – if I can be permitted this perhaps overly reductive word – came what is for me the high point of his career, those richly painted still-lives or abstracts of the late 1950s in which vessel-like shapes, as yet unformulaic, jostle and crowd together, sometimes like a mosaic, across a flat ground.

Although Scott represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1958, this monograph, coming six years later, must have further established his reputation. And it continued to grow. In 1972 he was accorded a full retrospective at the Tate Gallery; and in 1986, just three years before his death, Scott was not only given a retrospective at the Ulster Museum, Belfast, but also won First Prize (shared with John Hoyland) at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. More recently, his reputation has been crowned with a four-volume catalogue raisonné, edited by Sarah Whitfield, who also published in 2013 a comprehensive account of his life and work. This steady crescendo in fame owes much to this initial monograph, which, with its modern design, laid out the art of William Scott in a most enticing manner.

Frances Spalding

Frances Spalding is an art historian, critic and biographer. She is the author of a centenary history of the Tate and of British Art since 1900, as well as much-acclaimed biographies of Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, Gwen Raverat, the poet Stevie Smith, John and Myfanwy Piper, John Minton and Prunella Clough. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, an Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Art and Professor of Art History at Newcastle University, and in 2005 was awarded a CBE for services to literature.